One of the standout tracks on the new album, ‘All My Favorite People’ deals directly with the dichotomy. “I came out with it as I surveyed my own life and my whole family. Karin and I looked at each other one day, and one of us said ‘All my favorite people are broken.’ And we explored that. I worked on the song over the course of a couple of years, figuring out what’s trying to be revealed.

“I was working on a line: ‘I see each wound you have received as a burdensome gift;’ and whenever we make a pronouncement like that, a good editor will step in. We edit each other, and often find ourselves reframing our songs in terms of questions, and Karin made a slight tweak. She changed it to: “Is each wound you’ve received just a burdensome gift?” It’s just a subtle shift of what’s happening in terms of the conversation, where I’m putting the question out there: Iwonder about this, Ithink I’m learning something about this – what are you learning? And those kinds of conversations are what we are really interested in.”

In an industry where acts come and go with regularity, remaining a viable entity for two decades is a remarkable achievement. How has Over The Rhine endured? “Fortunately, we have people that have stuck with us from the very beginning. And along with that we have people that continue to discover the band every time we release a record. People are still finding out about us.

“Our audience is pretty diverse. If we play a concert that’s restricted to 21 and over, we will usually get emails from kids in college saying “are you sure there’s no way we can get in?” That’s maybe the most encouraging part of the equation; that young people are still getting excited about the music.”

With radio no longer able to break acts, and brick and mortar stores carrying fewer CDs, traditional methods of reaching an audience no longer apply. “A lot of it is word of mouth, and a lot of it revolves around our vision of connecting directly with our listeners. We were one of the first bands in America to have our own website. It was a kid at MIT that set it up for us and we barely knew what it was. It had a URL of about 46 characters; we kept it on a server at MIT’s campus.”

From the start, they took a hands-on approach. “We were stapling together hand-written newsletters and mailing them out, and really trying to not let other people do that work for us. Even if we were signed to a major label, we wanted to maintain a direct connection.”

From the start, they took a hands-on approach. “We were stapling together hand-written newsletters and mailing them out, and really trying to not let other people do that work for us. Even if we were signed to a major label, we wanted to maintain a direct connection.”

That connection is largely responsible for The Long Surrender. “When we realized we were going to be making this record with Joe, we looked at different options for funding, and decided to go directly to our fans; to tell them about this opportunity and invite them to step in and fund this record and make it with us.

“That could involve pre-ordering a CD at $15, which meant you would get the CD couple of months before it came out in stores, your name listed on the band’s website, and bonus tracks, all the way up to $10,000; where we’ll come do a private concert, put you on our guest list for a year, and give you a whole bunch of other treats.”

They had takers at every level. “We had a little over 2,000 people participate. One couple in Austin, Texas pitched in ten grand. We’re going to go down there in the spring and play a show in their barn for them and their friends. We just had one taker at that level, but the important thing is we got the entire project paid for, and we got to treat it as a barn raising, or a community effort.

“I think people really appreciated being part of process and seeing it come together. We sent the demos out to a lot of the donors, so they got to hear sort of the early versions of these songs, hear some of the songs that didn’t make the final cut, and be part of the whole process.”

The new business model is a radical departure from the past. “It’s extremely preferable to having a record label loan you the money, and then take 80% of the proceeds forever. Nowadays, there is no middleman; it’s really just us and you. It’s a fairly new idea, but other songwriters have done it, and it made perfect sense.’

The choice of Joe Henry as producer was inspired. In addition to his own catalogue of stellar solo releases, over the last decade he’s become a producer of note, with Solomon Burke, Bettye LaVette, Aimee Mann, Mose Allison and others benefiting from his skills behind the board. The paring with Over The Rhine is a natural; Henry is willing to mix things up, creating a unique blend informed by what has come before while offering fresh takes on long-established artists.

The choice of Joe Henry as producer was inspired. In addition to his own catalogue of stellar solo releases, over the last decade he’s become a producer of note, with Solomon Burke, Bettye LaVette, Aimee Mann, Mose Allison and others benefiting from his skills behind the board. The paring with Over The Rhine is a natural; Henry is willing to mix things up, creating a unique blend informed by what has come before while offering fresh takes on long-established artists.

“Like a lot of people, we had been noticing the records that he was producing, and we were getting really interested in his gifts as a producer. I loved the Solomon Burke records and the stuff he had done with Elvis Costello and Allan Toussaint, but I couldn’t quite figure out what that would mean for Karin and I. And we loved that idea of not being able to imagine the record in advance. It was a bit of an unknown, and that’s very exciting – when you trust a person – it’s very exciting to open yourself up like that.”

“Joe is a great writer, and there was an intuitive connection on that level. But there’s fearlessness; an element of danger about what he is doing. He’s not necessarily approaching it as ‘how do we make this an easy experience for the listener?’ It’s more like: ‘let’s blow the seams out of the songs.’

“We sent him all the demos and he had great feedback. He had this list; a couple of nudges here and there in a certain direction, but he put most of his work into carefully assembling the players for the record. Most of the hard work went to figuring out who needed to be in the room. He got an amazing group of players that really wanted to tune into what Karin was doing. And then he steps back and very gently orchestrates the proceedings. We were able to do what it is that we do; sit at the piano and play these songs with complete commitment and abandon. It was like leaning back into a great comfortable chair. We were effortlessly swept away, like we had been put on a train after dark; everything just started to move out of the room. It’s hard to explain, but it was embarrassingly easy to make the record,” he laughs. “We didn’t labor. We started on a Monday afternoon and wrapped up the following Friday afternoon.

“Joe kept track, and at least six or seven of the tracks on the record were first takes.” Like old school sessions, everything was live off the floor. “Everybody was playing together. If we did do a second take, Karin sang the entire song again every time.”

In every case, the vocals are entire performances, from start to finish. “Those are complete, intact performances. No overdubbing. Karin sang all that stuff live.”

They co-wrote two songs with Henry. “When we showed up at the sessions, Karin had one song that we felt really belonged on the record musically, but she just had one word, and the word was ‘soon,’ and I think it was Thursday, we were almost done, she asked Joe if he’d want to take the shot at writing the words.

“So before breakfast she had that lyric in her inbox. She made a few tweaks and we went in and sang the song. And it’s got some of my favorite lyrics on the record.”

While the musical component is obvious, Henry’s personal life made an impression as well. “When we were exploring the idea of making a record together, Joe mentioned that his parents were going to be attending one of our shows. It was a coincidence; they had heard us on one of the NPR stations and we were playing in Shelby, North Carolina where they live. Joe wrote a short tribute to his parents, because he knew that I would be meeting them. And I remember responding and saying what a rare pleasure, to read such well articulated love. I just couldn’t believe that Joe would take time to send me this letter in appreciation of his parents, in advance of us having the opportunity to meet them.”

That initial impression was cemented after Detweiler and Bergquist traveled to Henry’s home in California for the recording. “It’s a special family, where encouragement, support, and love are the order of the day. I’m sure they’ve had their difficulties along the road, like anyone has. But it’s been a gift to see a family care for each other so well. That was the atmosphere we were in while we were making the record at Joe’s house; you can’t help but encounter the whole package”

“And then, seeing the attention Joe pays to the details of his life; he can make an incredibly good cup of espresso,” he laughs. “Whether it’s that, or it’s the music that he chooses to listen to at dinner time – he mostly listens to older traditional jazz records and sometimes he’ll play songwriters, but I found it to be incredibly inspiring. It was kind of the week of a lifetime. It’s been an amazing new friendship. We really enjoyed that process and look forward to more.”

When I spoke with Karin back in 2006, the couple was in the process of healing after a particularly rough patch in their marriage. They’re still together, and thankful.

The album that precipitated the break (Ohio) was one of their strongest. Artistically, they were on a high. “That’s the thing; we got so caught up in touring and everything that was happening around that particular record that we just kind of ran out of gas when it came to loving each other apart from all of that.”

Rather than continue, they called off an important tour. “We shut it down for a little while, went home and kind of recalibrated. When the momentum begins to build for a relationship to blow apart, it can be a real challenge to find that fresh beginning. And I think we were part of the fairly small minority that were able to turn it back around and make a fresh start.”

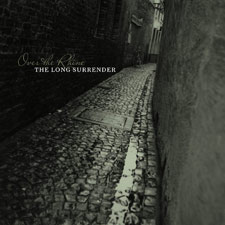

The new album’s title; The Long Surrender, speaks to the realization that life can be hard, and issues sometimes ongoing. “I think it’s universal. And when it comes to Karin and I, the biggest take away from that chapter was the fact that we had two things that we were nurturing simultaneously; a marriage and a songwriting partnership. And they both require a certain amount of creativity and care and commitment. We made the mistake when we were younger of thinking that if the songwriting is humming along, then we could put the marriage on hold indefinitely if we were on the road or whatever. Learning to balance both – taking care of both – on an ongoing basis is something that we continue to experiment with. But I’m extremely grateful that we’ve made it work.

The new album’s title; The Long Surrender, speaks to the realization that life can be hard, and issues sometimes ongoing. “I think it’s universal. And when it comes to Karin and I, the biggest take away from that chapter was the fact that we had two things that we were nurturing simultaneously; a marriage and a songwriting partnership. And they both require a certain amount of creativity and care and commitment. We made the mistake when we were younger of thinking that if the songwriting is humming along, then we could put the marriage on hold indefinitely if we were on the road or whatever. Learning to balance both – taking care of both – on an ongoing basis is something that we continue to experiment with. But I’m extremely grateful that we’ve made it work.

“Karin and I always had really good chemistry musically, and that was the first sort of connecting – music was what connected us initially, and then we realized that we were in love. And so I don’t know if they’re completely intertwined at this point, or if one could exist apart from the other. But let’s hope that we never have to figure all that out.

It’s clear that Over The Rhine’s audience is a vital part of the equation. “We’ve described that as people inviting our music to be part of the big moments of their lives,” Detweiler explains. “When that begins to happen, a deep relationship begins to form.”

He recalls a defining moment early on in their career. “We were getting a lot of letters, and I remember one day spreading eight or nine different letters out on a table, and it spanned a lot of human experience, beginning with: “I just wanted to let you know I fell in love and met my fiancée in college and this particular record was sort of our personal soundtrack for all of that.” That would be one letter. Then the next letter would be: “We were married last month, and we danced our first dance to this particular song on this particular record.” The next letter would be: “We took your records to the hospital; we were giving birth and they played them continuously, so you were there in spirit.” And I remember this letter from an old Irishman in particular, he had gone into the hospital to have surgery for cancer, and he took one of our records, and a couple of songs in particular that almost functioned as guardian angels for him, as he listened to this music in the hospital. And then the last letter was talking about burying a loved one, and a particular song the family had embraced as a mile marker for that season of loss.

“We were looking at each other, and obviously some writers and artists have various concerns when it comes to making a living – achieving a certain amount of recognition so that you don’t have to worry about paying last month’s bills – but on the other hand, we realized: what greater reward could there possibly be than to have the music finding its way into these big moments? Really: what more can we ask for? That’s continued to happen, and as long as we feel like we’re doing good work that people are continuing to embrace on that deep level, it’s enough to keep us going.”