As promised last week, I would like to use OttawaWatch, the next few weeks, to look at some ideas that might be radically conflict-resolving and that might take a few years or even decades to implement.

This past weekend

As a result of the political activities of the past weekend we have a new ball game, at least insofar as the two opposition parties are concerned. At their convention, last weekend in Montreal, the New Democrats moved to emphasize social democracy more and democratic socialism less than they have done before.

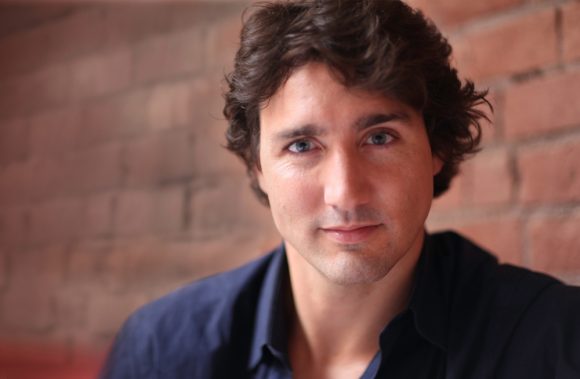

And Justin Trudeau, at 41, has taken over the reins of the Liberal party.

Both parties show few signs of uniting the left, in a mirror image of what happened in the Conservatives almost a decade ago. That was when the five or six different streams of conservative policy came together under Stephen Harper, with a little help from Peter MacKay.

So, in the run up to the 2015 federal election, it is likely that the struggle will be twofold. On one hand, the Mulcair NDPers and Trudeau Liberals will duke it out for control of the ‘Laurentian elites.’ On the other, the Conservatives will continue to broaden their base both centreward and rightward.

The Big Shift

They hope to build on the ‘The Big Shift,’ which was outlined in some detail earlier this year by Globe & Mail columnist John Ibbitson and pollster Darrell Bricker, in a book by the same name.

That tome suggests influence in Canada has shifted from those aforementioned Laurentian elites, so named for that belt of rocky hills and lakes that became the Ottawa/Toronto/Montreal axis. Ibbitson and Bricker acknowledge that it was around this axis that the nation was built, but point out that the influence in the last few decades has been toward the growing west and the large immigrant populations settling both there and in the suburbs of Toronto.

There is much more to this discussion, of course, and a look at The Big Shift will help to bring some focus to the complexities of these fairly seismic changes.

But the radical conflict resolution discussion I would like to encourage among OttawaWatch readers goes well beyond the effect of these seismic shifts.

One sidelight in Ibbitson’s and Bricker’s thinking that might hint at the hesitancy on the part of the Liberals to simply move in with the NDP is the existence of what they call the ‘John Manley Liberals’ those in that party who would sooner co-exist with the centre-right than with the centre-left.

The adversarial arena

The aforementioned seismic conditions go to the issue of the adversarial political arena that the shifts tend to amplify, rather than reduce.

Simply put, the job of the government is to govern and ensure that its governance is understood. The job of the opposition is to oppose and to ensure that voters know it is a government-in-waiting. Throughout 45 years of observing this setup, I have often tried to concoct scenarios that would enable people charged with governance and opposition to find ways to conciliate and collaborate.

The respective roles of government and opposition get complicated, however, when conflict-creating objectives almost hijack the debate or discussion process.

Safe discussions

My thesis, at this point somewhat oversimplified, is to encourage quiet, safe discussions in places that bring together the antagonists and their ‘handlers,’ to talk about the conflicts in ways that diffuse harm and engender understanding. It may be that doing this as a way of life might take a generation or two, just as it took about 40 years for William Wilberforce to end the British slave trade in the early 19th century.

And it may be, as well, that we are looking beyond the present political leaders to change the ways in which politics and governance can be done. ‘Radical’ innovations can be discussed in the kinds of safe places that are being proposed.

They could include such things as:

- Increasing use of early mediation to shortcut disruptive advocacy ‘theatre’ in the parliamentary arena.

- Convening of citizens’ assemblies to explore, in depth, parliamentary reforms that would diminish the destructive aspects of party discipline. Such an assembly occurred in British Columbia in the early 2000s. Its recommendations, tested in a referendum held in conjunction with the 2005 provincial election, fell just short of approval.

Bridging the divide

All of which brings us to something that is happening soon, in Montreal, that could start to encourage the kind of discussion to which I am referring.

Dubbed Bridging the Secular Divide: Religion and Canadian Public Discourse, this McGill University event will take place May 27 and 28. It will bring together several Canadian leaders and thinkers who are involved in faith-political discourse. Included are such people as:

- Mark Adler: Conservative MP and co-chair of the All-Party Interfaith Fellowship.

- Andrew Bennett: Ambassador of Religious Freedom, Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade.

- Janet Epp Buckingham: Director, Laurentian Leadership Centre of Trinity Western University.

- Bill Blaikie: Former NDP federal deputy leader and director of The Knowles-Woodsworth Centre for Theology and Public Policy.

- Wes McLeod: Former director of the Manning Centre for Building Democracy’s Navigating the Faith-Political Interface initiative.

- Lori Ransom: Senior advisor for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

- Joe Comartin: NDP MP and Deputy Speaker of the House of Commons.

- John McKay: Liberal MP and former National Prayer Breakfast Chair.

- Lorna Dueck: Host of Context with Lorna Dueck television documentary feature show.

These are the names that I believe might be most familiar to OttawaWatch readers. They will be interacting with others from Christian, Jewish, Muslim, native spirituality, Baha’i, Buddhist and Sikh backgrounds, all of whom have experience in interfacing with thinkers, communicators and policy-makers in other traditions than their own.

This next paragraph is taken from the description of the McGill conference, which is available at www.bridgingthedivide.ca.

This conference will explore the role of religion in Canada’s public discourse, in terms of both thought and action. To many observers it appears that our national discourse is increasingly polarized and the civility of democratic deliberation is eroding. Fundamentalisms of many stripes ideological, religious and secular can drown out the more moderate and considered voices. Within this context, how should perspectives that draw from religion inform the national conversation? How do we judge the legitimate and illegitimate role of religion in our public discourse? How can engagement by religious voices make positive contributions to our pursuit of the common good for all Canadians? Where does responsibility rest for changing the current state of affairs? These are questions that call for reflection on both values and practice, as we explore together how to bridge the secular divide.

In case the point is missed, my reason for including this information in a column about reducing political tensions is that frequently religion or faith is seen as both a divisive and a reconciling factor in public affairs. I hope this might be seen as one way of highlighting faith’s reconciling effect.

The role of pluralism

And, one last point: for those who believe that too much inter-faith or inter-ideology talk is to be avoided, I would recommend a reading of Canadian Brian Stiller’s recent blog on an understanding of pluralism, available at www.dispatchesfrombrian.com. The blog is entitled Reminding those who debunk pluralism: What it really is.

Stiller is currently global ambassador for the World Evangelical Fellowship, a role he took on after years as president, first, of the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada, then of Tyndale University College and Seminary.