“Proclaim the gospel at all times; if necessary use words.”

We hear this gem from St. Francis of Assisi often these days. The phrase is introduced as an encouragement to good works, but also, commonly, to subtly disparage proclamation of the gospel.

Two new books insist that St. Francis would never have said those words — didn’t say those words — but at the same time lived out their spirit.

Winnipeg pastor Jamie Arpin-Ricci loves to immerse himself “in all things Francis.” Not only is he part of a lay order in the Franciscan tradition, but he has just written The Cost of Community: Jesus, St. Francis and Life in the Kingdom, which describes how his Little Flowers Community tries to live out the teachings and example of Jesus, as St. Francis did himself.

In a very different book, Paul Moses details in The Saint and the Sultan the fascinating tale of how St. Francis went to speak with Sultan Malik al-Kamil in the Nile Delta during the assault on Damietta in the midst of the Fifth Crusade.

Together, these two authors remind us why Francis made such a stir in his own time and why so many over the intervening nine centuries have found him a compelling figure.

The Cost of Community

Arpin-Ricci says “it has been a trying journey thus far,” living in community in Winnipeg’s rough inner city. Members of the Little Flowers Community are “slowly and at times clumsily beginning to let [their] lives and ministries be more intentionally shaped and guided by the Sermon on the Mount” — with St. Francis as their guide.

Arpin-Ricci says “it has been a trying journey thus far,” living in community in Winnipeg’s rough inner city. Members of the Little Flowers Community are “slowly and at times clumsily beginning to let [their] lives and ministries be more intentionally shaped and guided by the Sermon on the Mount” — with St. Francis as their guide.

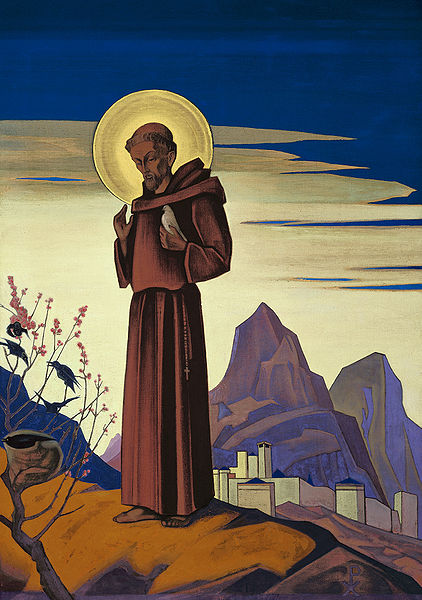

Born into the Middle Ages in Italy, Francis (1181-1226) would have been surrounded by signs of the dominance of the Christian church. Yet, like most people today, he was far from being a disciple of Jesus Christ.

Following a traumatic battle with the neighbouring town of Perugia, and then incarceration in that city, Francis underwent a radical conversion. Leaving behind a comfortable home and a devotion to the chivalric military ideals common to his class, he began to wander the countryside with only the clothes on his back. Though scorned by his family and most former friends, he soon began to gather a circle of followers, who were drawn by his devotion to following a simple lifestyle.

Arpin-Ricci, in turn, has gathered a community about him as he follows the lead of Francis. Little Flowers Community grew from a few regulars who used to meet at his home and in the neighbourhood.

Following Jesus in obedience is the cross we must take up daily, says Arpin-Ricci, and that is what he and his community are trying to do. “What emerges from that obedience,” he says, “is the very kingdom of God breaking into the broken reality of our lives, our neighbourhoods and the world to shine as a living alternative of hope and salvation.”

He writes with considerable humility, acknowledging that the members of the community often fall short — though most readers will no doubt be impressed with the way he and his friends put their faith into practice. “If we are honest, all of us are looking for ways to minimize or avoid the true cost of discipleship. As G.K. Chesterton — himself a great fan of Francis — so poignantly stated, ‘The Christian ideal has not been tried and found wanting; it has been found difficult and left untried.'”

Arpin-Ricci is not shy about the need to proclaim the gospel. That was Jesus’ way, and according to him, “Proclaiming and living the gospel were tied together intrinsically.” And Francis followed the lead of Jesus. “Francis (like Jesus) preached wherever he went. St. Francis never elevated action over speaking in the task of bringing the gospel to others, but neither did he believe that the gospel message was fully communicated only in words.”

He says that “Allowing this dynamic tension to exist is critical for us at Little Flowers Community.” The poor, he adds, “are able to spot hypocrisy from a mile away.”

Arpin-Ricci compares setting up Little Flowers Community in Winnipeg to St. Francis setting out on a journey to plead with Sultan al-Kamil. While admitting that inner city Winnipeg “is by no means as dangerous as the fierce battleground of a thirteenth century crusade,” he says that for those who chose to move with him into that community, “there has been the willingness to give up the privilege and security of the familiar… for the relative costs and dangers of an inner city community.”

The Saint and the Sultan

Paul Moses tells us in The Saint and the Sultan “to be skeptical about the tendency in our day to re-cast Francis as a medieval flower child, a carefree, peace-loving hippie adopted as the patron saint of the Left. Francis was far too devoted to suffering, penance, obedience and religious orthodoxy” for that.

Paul Moses tells us in The Saint and the Sultan “to be skeptical about the tendency in our day to re-cast Francis as a medieval flower child, a carefree, peace-loving hippie adopted as the patron saint of the Left. Francis was far too devoted to suffering, penance, obedience and religious orthodoxy” for that.

Instead, the author insists, he was “on a quest for peace — a peace encompassing both the end of war [Crusades] and the larger spiritual transformation of society.” That is how he found himself in the sultan’s court in Egypt. But his relationship to Islam and the Crusades was distorted or covered up by biographers who wished to stress his saintliness and his desire for martyrdom, and who were eager to curry favour with the powerful medieval popes who organized the Crusades.

The Saint and the Sultan — which has been well received by both Catholic and Islamic scholars — tells the story of how Francis undertook his daring mission to end the Crusades. In 1219, in the midst of the Fifth Crusade, Francis crossed enemy lines to gain an audience with Malik al-Kamil, the Sultan of Egypt.

The two talked of war and peace and faith, and when Francis returned home, he proposed that his Order of the Friars Minor live peaceably among the followers of Islam — a revolutionary call at a moment when Christendom pinned its hopes for converting Muslims on the battlefield.

Cardinal Pelagius Galvani, who was sent by the pope to lead the siege on Damietta, believed that “souls were to be won at the point of the sword.” Francis strongly disagreed, but he did not oppose preaching the gospel to those outside the faith; he risked his life to tell the sultan about Jesus Christ.

Moses quotes this passage from Francis as “the heart [of his] instruction to his followers for approaching Muslims”:

“The brothers who go can conduct themselves among them spiritually in two ways. One way is to avoid quarrels or disputes and to be subject to every human creature for God’s sake, so bearing witness to the fact that they are Christians. Another way is to proclaim the word of God openly, when they see that it is God’s will, calling on their hearers to believe in God almighty, Father, Son and Holy Spirit, the Creator of all, and in the Son, the Redeemer and Savior, that they might be baptized and become Christians.”

Francis was a peacemaker, and believed that the best way to change others’ behaviour was to lead by example. However, he was by no means shy of preaching the gospel.

The story of the saint and the sultan is almost a millennium old, but it remains as current as Armin-Ricci’s tale of the trials and successes of Francis’s followers in Winnipeg. How much more timely could a book about peace-making between the Western and Islamic worlds be? Christians in foreign or unreceptive cultures must not presume to act from strength, as the Crusaders did, and as many missionaries did during the time of Western colonial expansion more recently.

But we need not — dare not — be ashamed of proclaiming the gospel, whether we are abroad or in our own cities. St. Francis does have a lesson for us. He said, in effect, “Preach the gospel at all times. Use words; live out your faith.”